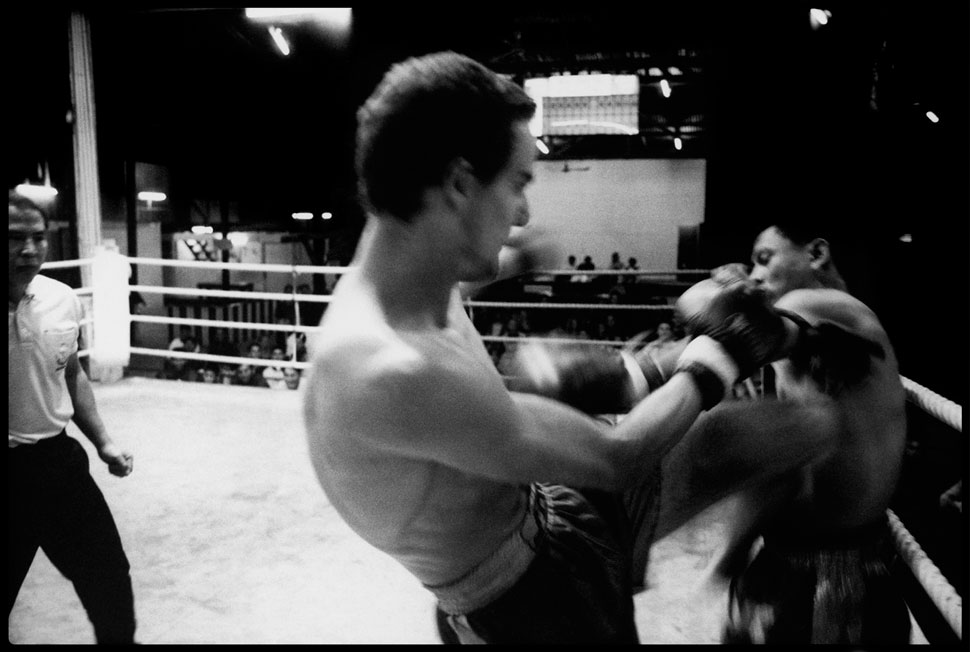

Accompanied by the strains of a Thai reed pipe and the clatter of cymbals, Halfdan climbed into the ring. His face slowly drained of colour. He took in exposed beams, corrugated roof, fluorescent light, opponent, teacher, then lightly gloved hands and below that, bare feet on dusty canvas. His first fight was about to begin.

Momentarily giddy as he straightened up, his focus anywhere but on the several hundred peopled gathered below, The cheers may have been for the bravery of a farang (foreigner) taking on a local fighter, Halfdan was no longer certain. He took little notice as the ritual music ended and his opponent started making his way across the ring towards him.

There’s something strangely compelling about a tale told through the slackened ropes of a Muay Thai kick boxing ring. Halfdan, as the name suggests, is half Danish. The other half, belonging to his French mother, gives the 19-year-old a rangy appearance. He tried his hand at karate for a couple of years before travelling to Thailand, attracted by their style of kickboxing. Before he knew it – and way before he was ready – he’d fallen into a drunken New Year’s bet and found himself preparing to fight a Thai kickboxer in a local tournament. The Lanna Muay Thai boxing camp, nestled at the base of the Doi Suthep mountains overlooking Chang Mai, Thailand’s northern capital city, became his training ground and his home.

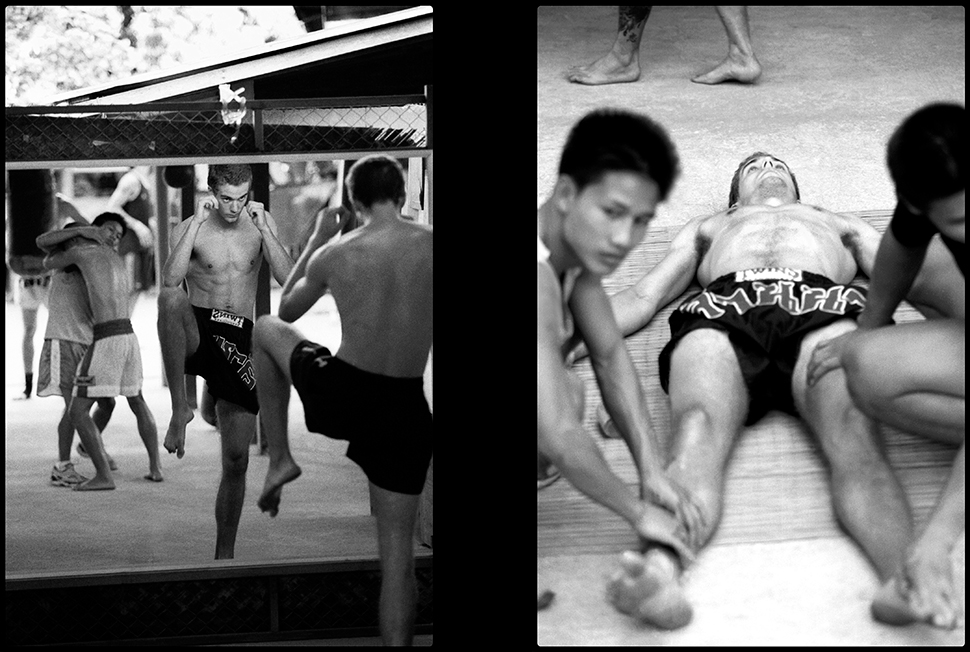

Halfdan preparing for his fight © Andrzej Liguz/moreimages.net. Not to be used without permission.

The swathe of farangs who make the trip to Thailand each year to live in such camps and test themselves against the local kickboxers are a dedicated group. It’s never enough to simply learn the moves. In a fighting culture where at one time every man, woman and child was schooled in Muay Thai, that approach will quickly get you taken apart. The farangs who are serious about it endeavour to do more than just scratch the surface of a fighting culture. Customs are adopted, rituals observed, and each fighter is accepted as a resident, rather than as a visitor on some sterile, guidebook-inspired tropical safari.

Co-owner of the Lanna – literally, “kingdom of a million rice fields” – Muay Thai boxing camp Andy Thompson, a Scottish/Canadian, is one of the first to have made a permanent home in Thailand in order to learn the secrets of the traditional battlefield art. His Thai wife Musaba “Pom” Sukanon functions as day to day boss at the camp and de facto mother to the fighters. Through the ropes of his own training ring, carefully taped in red-white-and-blue stripes by younger members of the camp, Thompson reflects on the path he and many other farangs have taken: “I started training in Muay Thai when I was 32 and fought when I was 34, 35, – too old to become a champion. That’s why I decided to establish the Lanna Camp. I fell in love with the sport, fell in love with the kids, the boxers and thought to myself, I could do this, I can learn this, I can set it up.”

Samantha, tall and wiry – a Kiwi – joins Thompson at the ropes and talks counterpoint to the flesh smacking leather elsewhere in the gym: “I was working as an accountant for an airline. Since there’s little to do in Luton but drink, I was looking for something else to do a couple times a week. A friend of mine who trains police in self-defence told me Muay Thai’s the most effective form of self defence he’s ever seen. It’s all about just two or three moves rather than thinking, okay I’m gonna do this, I’m gonna do that. If you’re in a self defence situation, it’s a better form to use rather than trying to think of all the fancy moves you use with other martial arts.”

To illustrate, Sam backs up a step and hunkers down, hands weaving. “The two bits of self defence I would use most would probably be the knee . . .” up it comes – high and fast – to slap her opposite palm, “. . .and the elbow . . .” a twist and a step forward brings her intended blow back to the ropes, point of the elbow aimed at the bridge of Andy’s nose. “Because if you’re in a crucial situation where somebody’s grabbed you, they won’t expect you to use either and it’s very simple. It’s a quick move, then run very quickly in the other direction.” With a shrug, the Sam version of a hit-‘n-run makes her laugh.

Halfdan has reached the second of five rounds and is gaining confidence. His opponent is not a mismatch – Thai kick boxers respect good sportsmanship and fair play above all else and, while dangerous, bouts are never one-sided affairs. Close contests being good contests, and limited by the ring, Halfdan’s trying not to adopt Sam’s hit-n’-run tactics. He and his opponent test each other early – probing, patient – then trade blows in a flurry. A knee drives into a stomach, a foot crashes into a chest, Halfdan protects his head and finds himself fleeing one moment, chasing the next. A drunken man with money on the outcome tries to climb into the ring and is led away. The shouts grow louder, the round ends, Halfdan’s seconds cannot say who’s winning, but he feels good, he feels good.

Thompson continues, as does the morning’s sparring between local Thai’s and overseas residents: “I decided to make Lanna Camp different to the way other camps are run in Thailand and focus it more on individual responsibility. You need a lot of self-discipline to do this because no-one’s standing here going ‘work-work-work, train-train-train.’ It’s up to you. If you go to Bangkok you’ll see the way they train in the gyms; pushing the fighters hard. That’s okay, but ultimately the guys here will be happier. And if they prove themselves to be good enough, if they work hard enough and want to go all the way to the top, then by all means, we’re going to be there. We’ll be working with them, we’ll be pushing them.”

One man who may indeed go all the way to the top is Canadian Eddie De Nobrega. Unlike the American kick boxing Eddie’s used to, Muay Thai allows the use of elbows and knees, which makes it the most brutal of the full contact martial arts -no doubt the reason it’s banned in Eddie’s home country. At 26 years of age, Eddie made the move to Lanna Camp and has made it his home for the past 12 months. A smooth looking character who – and this is quite rare – has won his last four fights with a k.o, Eddie may just be the great white hope of Muay Thai: “I used to run a big nightclub in Toronto and when I quit that job to do this, everybody told me I was crazy. But I didn’t feel that way about it. I hated the late hours and the scene, everybody’s always drinking and it’s always a party atmosphere. I just like doing this so much more. Now I don’t make a lot of money but I’m happy and that’s far more important.”

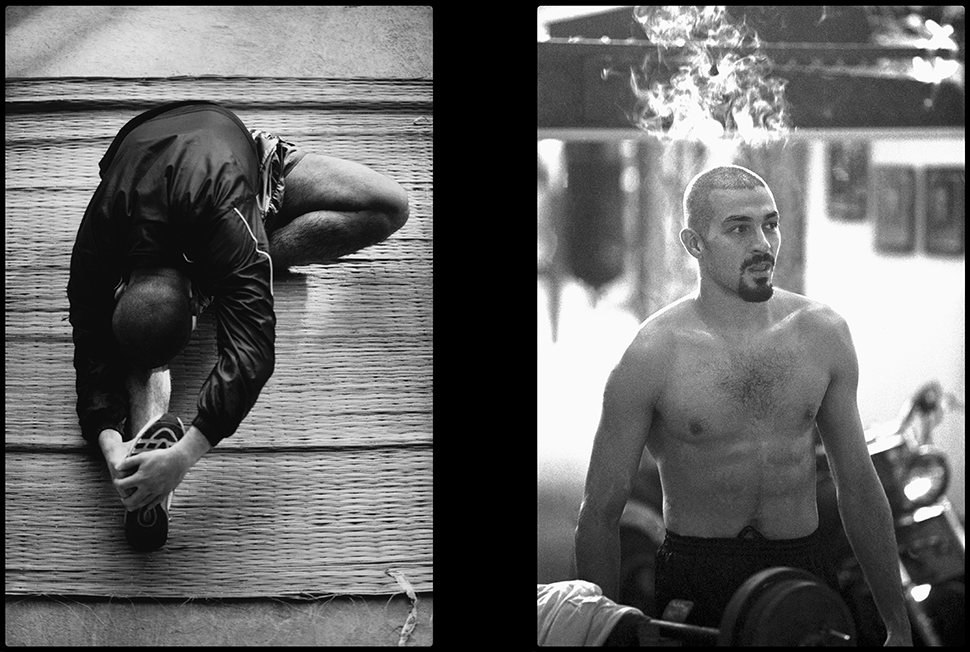

Ahmed Ait stretching / Edward de Nobrega steaming after an early morning run © Andrzej Liguz/moreimages.net. Not to be used without permission.

Pausing for breath, steam slowly rising from his torso, Eddie flips his sweat towel over the free-weights rack on the sandy gym floor, spreads his hands and continues: “I’ve asked myself many times what I get out of it. The training’s hard, the fighting’s hard. I always say I’m in the best shape of my life, but I can barely walk down the street. I asked one of my Thai friends why he does this and he told me it’s the pursuit of excellence. They quote that as much as possible and I think that’s the essence of why we all do this. It’s really hard training, but when you win you feel awesome. Once in a while someone gets cut with an elbow or something, but not too often. A lot of people have problems with their legs because they kick with their shins, and then the legs get messed up – knees and stuff like that.” Eddie is serious about his workouts and settles back beneath the bench press bar. As an afterthought he adds: “The worst I’ve seen is someone get kicked in the leg and the leg just snap and break. Some people, like boxers, get head damage.” His knuckles brush the gym floor briefly. “It’s kind of scary, so I try not to think about that too much.”

The young Thai kickboxer has worked out Halfdan’s moves and is beginning to tire him with devastating kicks to the legs. As he moves around the ring watching Halfdan, the Thai fighter swings his head from side to side like a snake about to strike. On the side of the ring where the serious betting takes place, Eddie observes that Halfdan isn’t blocking enough and will slow down soon as his legs begin to hurt. Each time he’s struck, Halfdan tries to counter by punching the Thai with his longer reach. The Thai’s counter is simply to keep smiling and weaving his head, as most Thai fighters do. Knowing that his kicks will score higher, he waits patiently for another chance to go to work on the farang’s legs.

Each fighter has very different reasons for being at Lanna camp. Another Canadian, Charles, is a youth worker with the Han Indian people, working with kids who get twisted on drugs and alcohol. He helps them knock themselves back into shape by training them in martial arts. Mario da Silva runs a gym in South Africa and is here with former South African super heavyweight champ Dimitri Bailamis on the comeback trail. Ahmed Ait, serious at 24 years of age, can be intimidating until he breaks into a smile. Born in Morocco but raised in Norway, he’s been training at Lanna for about eight months and says he’s “gonna be here for a while.”

Stocky, 27-year-old American Gabriel Miller uses R&R from the US Army to drop in on Lanna camp: “This is probably the most effective stand up form of martial arts there is. Uses the knees and the elbows, has the strongest kicks. Doesn’t use a lot of flashy stuff. Just the stuff that works, which is what I want in the military. It’s probably the last martial art that’s really stayed with its roots. In the heat, in the rain, they still do the dances and rituals. So it’s stuck close to its traditions, even though it’s branching out to the rest of the world.”

The lone Australian at the camp sports tiger-style dyed hair. 23-year-old Chris from Mandurah, WA, has been boxing for about four years. “I started training just to get fit and then progressed to going into the ring and having a go. I’ve been working in a hardware store for a while and I’m really lucky because they gave me six months off so I could come here to train as I want to turn professional one day.” The biggest centres for the sport in Australia are in Melbourne and Sydney, although it’s growing in popularity in Perth. Dominic, a 22-year-old tattooed French Canadian who used to work in an abattoir explained why he’s into Muay Thai; “I figure it takes a lot of courage to make it through life. If I can find the courage to get in the ring, then I’ll probably have the courage to do anything.”

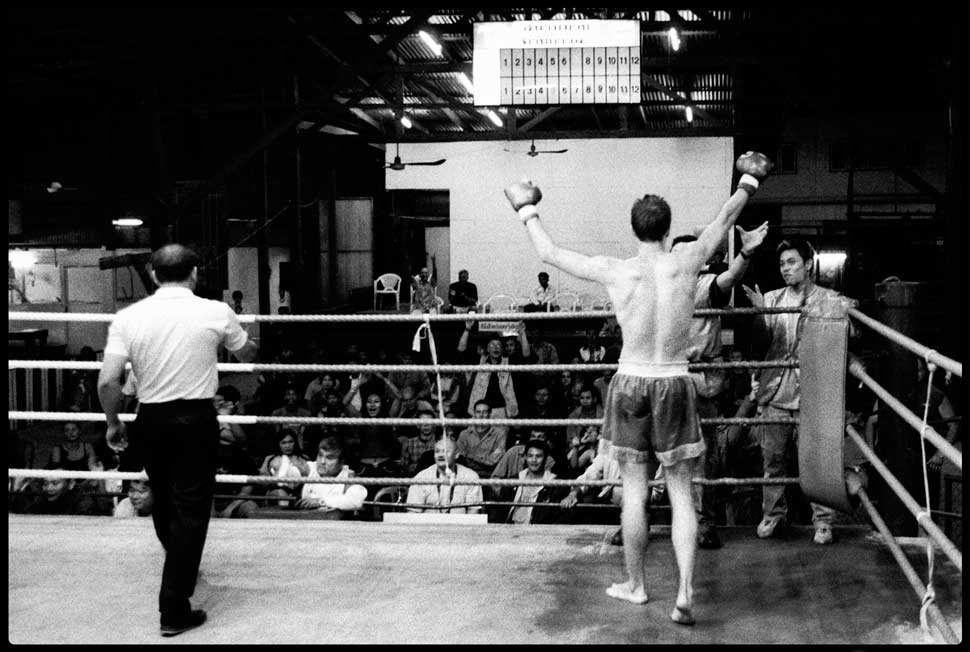

Halfdan raises his arms to the audience at the end of his fight © Andrzej Liguz/moreimages.net. Not to be used without permission.

At fight’s end, Halfdan is elated. He felt he regained some control of the bout and the last round was his best. After managing a ritual “wai” salute to each judge and the referee, he stumbles to the opposite corner to receive the traditional drink of water from his opponent. Turning, gloves raised to acknowledge the cheers of the other farangs not brave enough to step into the ring, Halfdan doesn’t notice the referee raising his opponent’s arm in victory. The high-scoring kicks have taken their toll. Only after the stadium cleared and he asked his companions about the money they bet for him did Halfdan realise that a close points decision had not gone his way. There would be nothing in the kitty for the night’s celebrations. But . . . he had made it through. He knows he’ll be back.

See the complete photo essay accompanying this story.

Words and pictures © Andrzej Liguz/moreimages.net. Not to be used without permission.